I have a passion for teaching people stuff. I get a buzz from helping people learn what I know, and then watching a person become empowered with that new knowledge.

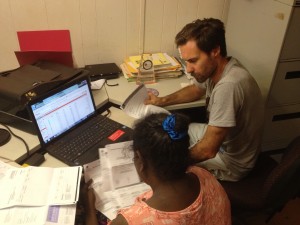

Working as an Enterprise Facilitator in Galiwin’ku, I find myself trying to teach people things all the time. I believe that if Yolngu have access to all the information Balanda have, in a form they wholly understand, this would be a huge step toward lasting empowerment. So everyday I’m looking for teaching opportunities, to be giving people this ‘Balanda’ information, whether it be how to do a budget using Excel, buy something online, put ink in a printer, or explaining law requirements for running a business.

Unfortunately though, my zeal for teaching led me astray. I forgot the bit about ‘in a form they wholly understand’. I catch myself, all the time, being the one doing all the talking or being the first one to jump in with the answer. I fall into the trap of thinking I have all the answers and that if I repeat myself many times or just speak a bit louder, then people will understand my English gibberish. A lot of the time, I walk away from a situation like that wondering whether what I have said has made sense, wondering whether that vital information has been absorbed. I soon find out it hasn’t.

Have we assumed ignorance?

The great educator Paulo Freire coined this limited style of teaching as the ‘banking’ concept of education. Without even realising, I had made myself into an education banker. I was attempting to make huge deposits of valuable information into the presumably ‘empty’ minds of my students. I was going to make them rich in knowledge. Freire describes this method, “In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing.”[1] I had automatically and without question, assumed the ignorance of those I was engaging with. I was the superior Balanda holding all of the knowledge, and they were the inferior Yolngu who needed to hear and absorb the gold I was throwing at them. This approach is simply not effective. People tend to only hear half of what is being said, they feel inadequate to learn, and both parties walk away feeling frustrated that they haven’t understood one another.

Recently I have been helping a group of Yolngu women who run a corporation. We have been discussing the word ‘governance’ and what ‘governance’ looks like for them as a group of Yolngu people who are trying to operate in a Balanda business setting with their Yolngu cultural worldview. Over the days of discussing governance, one of the women showed me some important paintings, which to me didn’t make any sense. “This is our governance,” she told me, pointing at the paintings. OK… nice paintings, I thought. Then, later that day, the same woman started telling me a story about the Dingu (Cycad) nut. This nut is harvested from the Dingu tree, ground and treated to make traditional flour. She explained to me the different roles that the different clan groups had in processing Dingu. One clan was responsible for harvesting the nuts, another for grinding the nuts and so on. OK… nice story, I thought. So it took me a while, but eventually I realised that she was using these stories to explain to me what Yolngu governance is. She wanted to show me the important artworks that represent the law and relationships between clans, the governing factors within her community. She wanted to give, as an example, the traditional system already in place to dictate the production of flour from the cycad nut, to show me, “Hey, WE KNOW GOVERNANCE”. Oh, how humbling it was when I finally clicked: these guys already know what governance is… I had been assuming that I was starting from a blank page, an empty bank account into which I simply needed to deposit my knowledge of governance when they in fact already knew what governance was. To teach the concept, I needed to listen first.

Listen and learn first.

If I can understand the perspective and mindset of the person I’m engaging with, then I can start to discuss and teach a concept in way that is truly meaningful. It is so important to find out what someone already knows, whether it be traditional knowledge, existing Balanda knowledge or misconceptions about Balanda knowledge; This will be the seed from which new learning can grow. Start with what people already know!

Listening creates respect and trust. I must be proactive to help this two-way education take place. Before I try to teach anything now, or give a directive, I try to listen and be taught something first. I can ask general questions about Yolngu kinship, clan relationships, and stories in songlines or how to say a word in Yolngu Matha. This gives me some insight into people’s worldview as well as giving me information that can possibly be used as future teaching tools. When talking about a specific topic, a helpful question can be “what picture do people here see when I say the word ……..”. This helps me see what somebody knows (or maybe doesn’t know) about that topic, it gives me a chance to see the topic from their perspective, and start a dialogue. Asking these questions not only gives me a chance to learn something, it gives Yolngu people a chance to be the teacher. When I am the learner, it puts us on a level playing field. They feel empowered, and have a sense that they have something to give, because they do! Any teaching exchange then becomes more constructive because there is mutual respect.

How can I listen better?

Listening is not passive, especially in a cross-cultural setting. I’ve learned that to listen and understand well, I need to deliberately slow conversations down. Stop talking when it’s been a while since I’ve heard anyone else’s voice. Pause after sentences so people can let me know when they haven’t understood something. I need to ask questions that will provoke more than just yes/no answers and not put words into people’s mouths. To do this, I need to allow time for long conversations to take place. Let the discussion go off track if need be – the ultimate outcome will be a deeper understanding of each other.

In essence, I must see these people as intellectual human beings with a lot to give. Yolngu people are a wealth of knowledge. Stories, artworks and songs tell lessons of morality, metaphors with deep meaning that direct people to a way of living that encourages peaceful relationships, ways to care for a child or old person, proper ways to engage in business transactions and best use of resources. I must realise I do not hold all the knowledge. I must see Yolngu people as having a full bank account that I can make a withdrawal from, from time to time. I must be like an investigator who is trying to seek out what someone already knows and start from there. By listening and learning first I can let my zeal for teaching help in a way that will truly empower both parties.

Written by Ben Grygoruk

[1] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, (1970, Continuum Publishing Company), p.53.

Biritjalawuy •

Manymak dhawu ga yuwalk dhawu.

Great article.

Serge Gryroruk •

Well done SON well written great what your doing im so proud of you.

Narelle Grygoruk •

Good work, thanks for the insight…soo proud of you!!

Luke •

Well said! I’ve been working on communities in the central desert for the past few years. Despite doing a training with Richard last year i really appreciate the reminder about communication. Thank you

Tina •

Beautiful message Benny G, So glad Elcho is blessed with you and Jaz. Thanks for sharing your experience!!!

Ben •

great insights Ben, good to hear some of the work you are doing.

Kylan •

Great Article Ben!

alicia •

so well written x inspiring.

Justine •

Great article Ben. Thanks so much for sharing.